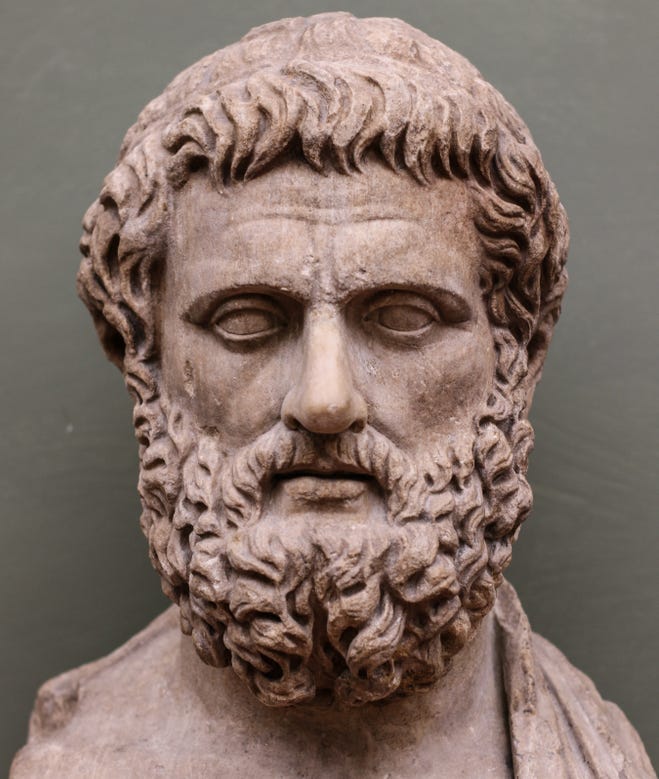

Intermission: Sophocles on Active and Passive

An Ancient Vision of Principles at the Heart of Political Life

(This is the tenth post of what is to be a limited series. I may already be more than half-finished with it; at any rate, I am taking a brief break from Plato and Thucydides with this post, and turning to Sophocles for a look at a theme that will prove relevant to my main focus. Previous posts can be found here.)

In a talk given in May 2023, the English intellectual Mary Harrington (whom we have encountered before) pointed to a question underlying many of the most bitterly contested political disputes of our time: what does it mean to be human? As she shows (beginning here), there are two basic understandings at play. The first is based in the old Christian notion of the imago dei – that is, of humans being made in God’s image. On this view of things, there is a definite human nature; ‘humanist’ medicine, as Harrington calls it, aims at bringing the body back to its natural state (e.g., by curing a disease or fixing a broken bone). Recent decades, however, have seen the emergence of a trans-humanist path, whose first moment came with the birth-control pill. This represented a new step, for all of a sudden, the aim was not to return the body to its natural state, but rather to improve upon that state by disrupting a natural process. This trans-humanist path sees human nature as a baseline from which we upgrade ourselves. There is no upper limit or known endpoint to this process of self-upgrading. The aim here is not attaining, but “mastering imago dei” (emphasis mine). Harrington says that every “scissor issue” today on which one cannot avoid taking a side turns on the dispute over what humans are: “Does normal exist? What is sex for? What is a woman? What is a mother? Are we entitled to opt out of normal developmental processes? Should we be free to modify ourselves as we see fit, and if not, why not? What, if any, are the limits to any of this?”

When Harrington speaks of mastery while describing the new view of what it is to be human, she brings up a matter that people worried over long before our own time. In the fifth century BC, the Athenian playwright Sophocles put the following words at the end of his play Oedipus the King: “do not seek to be master in all things.” Sophocles, no less than Harrington, was concerned with this sort of question: to what degree is it appropriate to aim at control, at mastery, and to what degree should one simply accept what happens? That is, how much of life should be activity, and how much passivity? We have just seen how such questions are of fundamental importance to our technological era, but the first, and perhaps the greatest, treatment of the matter is to be found in Sophocles’ play. At its most fundamental, the play is a reflection on activity and passivity, presenting a vision that goes to the heart of so much at work in our own time. (The theme of active and passive was not confined to Sophocles in his day; for its appearance in Thucydides and Plato see my book, p. 24 and pp. 263-265.)

We can start to see the central role of active and passive in Oedipus the King if we turn to the events around which it is built, the things that have already happened when the curtain rises. When Oedipus is born, in Thebes, an oracle declares that he will kill his father and have children with his mother. His parents, determined to avoid this outcome, hand him over to a shepherd, who is to kill him by exposure, but the shepherd takes pity on little Oedipus, beginning a series of events that see him brought up in Corinth. Years later, having grown up, Oedipus hears an oracle prophesy that he will kill his father and have children with his mother. In order to avoid this fate, he leaves Corinth for good. In the course of his travels, he encounters his real (i.e., biological) father, whom he kills, and he soon marries his real mother. The play begins after these events, and the action of the play is the process by which Oedipus comes to understand what has happened.

Already in this initial story, there are indications that the matter of active and passive constitutes a central theme. The action of a play typically involves some decisive series of events that brings about a new state of affairs. A prophecy, on the other hand, is normally just a kind of seeing, a fundamentally passive thing. But if we consider the series of events described above, we see that activity and passivity have traded places. The action of the play does not decide or change much of anything. All it does is reveal to Oedipus the truth about himself, revealing in the process that there is nothing that can done about it. The action of the play, then, occupies the passive role. The prophecy, on the other hand, plays a decisively active role. Oedipus only wound up fulfilling the prophecy because it was made in the first place: an oracle caused his biological parents to get rid of him, and an oracle caused him to leave Corinth, producing a situation in which he could encounter his real parents without knowing it, leading to the fulfilment of the prophecy. The actions of Oedipus and his parents, by which they try to avoid what has been foretold, are the means by which they become passively subject to their fate. It is because they think there is something to do that something is done to them; because they think they can act, they are acted upon; their belief that they can control things becomes the means by which they lose control. (The paradox is a typically Hellenic one.)

When I was teaching the classics, one theme I would bring out in numerous Greek tragedies was what I referred to as the “the natural and the rational.” The theme is essentially connected to the question of active and passive, and it allows us to be a bit more explicit about the sort of thing that is at stake here. The idea is that there are certain aspects of our lives that are determined for us by nature. For example, if one of your parents had a history a heart trouble, you and your siblings might find yourselves with similar problems – in fact, one could list at length attributes that we tend to inherit naturally from our parents (height, hair colour, etc.). You will always be bound to your natural parents and siblings, at least in the sense of sharing these attributes (and genes, etc.), in a way that you never can be to people you choose or happen to associate with. So we have on the one hand an aspect of each of us that is given to us passively, by nature – this is the ‘natural’ side – but there is also a great deal in our lives that we arrange actively, by thinking and choosing, and this can be labeled ‘rational.’ Of course all of this takes for granted that there is a natural order; a total mastery of imago dei would presumably leave all the talk of hair colour and heart attacks far behind.

Anyway, one thing to notice about Oedipus the King is that at its heart lies a natural abomination, a crime against the natural order: it is the story of a man who kills his father and has children with his mother – and we will see that this is to be directly connected to what is ‘rational’ in Oedipus.

I am now going to proceed to discuss some aspects of the action of the play, and while I hope my account can be read on its own by people who have never encountered the play, if you’re not familiar with Oedipus the King, why not go read it now? It should only take you an hour or two, it’s among the greatest works in the Western cannon, and reading it will enrich your understanding of everything I say below – you can even look up my references to the play’s line numbers! (Also, my preferred translation, by David Grene, remains available from the University of Chicago Press at an affordable price.)

If we are to sum up Sophocles’ Oedipus in one word, that word must be activity. He is a supremely competent person, a self-made man. He was the greatest of the citizens in Corinth (775-776), and later, having come to Thebes an exile, became king by solving a riddle which nobody else could solve (35-38), and along the way, single-handedly killed a group of five men who accost him (801-813; see also 752). At the end of the first scene he confidently declares: “I will bring these things to light ... from the beginning” (132) and “I will disperse this pollution from this land” (138); the play consists largely of the sequence of events according to which these claims are made good. Along the way, he pushes past the resistance of Teiresias (319-349), Jocasta (1056-1073) and the herdsman, using violence in the final case (1154). Clearly this is a man who gets things done.

When he has chosen a course of action, Oedipus wants things to happen quickly. Repeatedly, we hear him emphasise speed, using various forms of ‘fast’ (tachus – 143, 618-619, 765, 1154). Having sent Creon to Delphi, he wonders that he is not yet back (73-75); later he is similarly impatient for the arrival of Teiresias (289). When the people come to him at the start of the play, they find that he has already taken action; similarly, when the chorus suggest talking to Teiresias, Oedipus has already sent for him (284-289).

This swiftness, however, does not bring with it any lack of deliberation. On the contrary, Oedipus is a master of a certain kind of thinking. We have already noted his success in solving a riddle, in which his intellect prevailed where no other could (396-398). His decision to apply to Delphi comes only after much thought (67-69). Three times we see him cross-examine a witness – first Creon (85-132), then the Corinthian messenger (956-1046) and then the herdsman (1121-1181) – and in each case, he brings out all that he need to know as swiftly and as certainly as possible. He recognises at the beginning that the case of Laius’ murder will be a difficult one (110), but the play shows him correct in his belief that he needs only a small beginning to open it up (120-121).

We should pause to note how this intelligence is essential to the theme I set out at the beginning: activity. Only a person supreme in deliberative ability could be supremely active, for otherwise, his errors would soon hold him back; similar arguments obtain for such characteristics as courage, confidence and competence in general, and Oedipus does not lack these. His past successes make him confident – we have already noted his bold predictions (120-121, 132, 138) – but also give others faith in his ability on the basis of experience (44-45). Again, such confidence inclines him all the more towards activity. Thus Oedipus, in the combination of his temperament with his ability and the results of this ability, presents us with as full a development of the active side of the human character as there could be.

The kind of thinking that Oedipus employs is central to the play. His is the kind of mind that builds a bigger picture out of smaller clues. He says at the start that he needs only a small beginning (121): he approach is to sift through conflicting pieces of evidence, figuring out their relation to one another and thus the larger picture of which they are a part. (e.g., “Laius was killed at a triple crossroad? But I killed some men at a triple crossroads... could I have been the murderer?” – and soon the witness who can provide certain proof or disproof of this theory is sent for.) The ‘action’ of the play is his ultimately successful inquiry, but before he begins to figure out the truth, Oedipus encounters an altogether different manner of thought.

The first thing Oedipus runs into in his search for the truth is precisely the whole truth, and it blinds him. As soon as he gets Teiresias to tell what he knows, there it is: the old man tells him “you are the unholy pollution on this land.” (353) This is soon followed by other, more detailed aspects of the truth (366-367, 372-373, 379, 413-428, 438, 442, 449-460), and Oedipus is utterly incapable of grasping any of it. Because he runs directly into the whole truth rather than just a part, he is set upon the wrong path (readers familiar with Plato should think, at this point, of the image of the sun, which one cannot look at directly). Because it is revealed directly, rather than being pieced together from simple beginnings, it seems impossible, and so Oedipus searches for some different explanation. Obviously he is not the murderer – why would anyone say such a thing? This leads to the mistaken theory that guilt must lie with Teiresias. This episode puts the talk of small beginnings in a different light: Oedipus’ is the sort of mind which must have small beginnings. It can only arrive at the truth by working through smaller pieces, pieces of the sort which it can easily grasp, putting these together so as to work out the larger picture.

Teiresias represents a character precisely opposed to Oedipus. Oedipus is supremely active; Teiresias is passive. He moves about in a conspicuously passive manner: a blind man, he is led by a boy. His effort is directed at doing nothing: he tells us (358) that he only reveals the truth because Oedipus provokes it out of him. The course of the scene with Teiresias can be understood in reference to what we already know of Oedipus: as the supremely active man, he wants to know in order that he may act (note, for example, that at 785-786 that the reason – gar – he consults the oracle is not simply to attain knowledge, but to silence those who question his parentage). Nothing could be more incomprehensible to him than the position of Teiresias, who knows, and therefore wants to do nothing. Thus Oedipus swiftly becomes angry, and suspects the worst motives: the man must not be well-disposed towards the city (322-323); his aim was the betrayal and destruction of the city (330-331); soon enough, Oedipus accuses him of complicity in a plot to murder the dead king (346-349).

But Teiresias is no villain. Instead, he represents a manner of thinking and knowing precisely opposed to that of Oedipus. While Oedipus acquires his understanding by working through small beginnings, we never see any such work with Teiresias. On the contrary, he seems to have a sort of immediate, universal knowledge. In a certain way, he knows everything, but he forgets; to know any particular thing, he has to be reminded by something that happens to him. Thus among his first words, we hear him say “though I knew these things well, I lost them, for I would not have come here” (317-318). It is his contact with Oedipus that reminded him of the horrible truth about the man, and he only came because it was not before his mind with Oedipus absent.

Thus the confrontation between Oedipus and Teiresias is a confrontation of active and passive, and of related modes of knowing. Oedipus, it would seem, proceeds from parts to whole; Teiresias is moved in the opposite direction. Oedipus presents a superlative development of normal human knowing; Teiresias’ mode of knowing is akin to that of the divine, something typically allowed to humans only through inspiration, as in art or religion. Like Apollo, Teiresias is in immediate possession of the truth; normal mortals, if they can grasp it at all, must work to get there.

The encounter with Teiresias makes Oedipus more certain of his own manner of reasoning. He becomes convinced of the inefficacy of prophecy (357), and, as befits his mode of thought, he brings forth evidence, thus “proving” the inadequacy of Teiresias’ art (387-398). The opposition between the two thus reaches its furthest point.

In this opposition of active and passive we find the hamartia of the play – that is, the tragic flaw, the crucial moment of missing the mark. Oedipus represents only the active side of human character. What is missing is an adequate relation to the passive side, a fact given particular emphasis through the encounter with Teiresias. When Teiresias asks, “do you know who your parents are?” (415), he brings before Oedipus that part of his identity to which there can be only a passive relation: the natural side. One does not choose one’s parents; there is nothing one can do about them. Oedipus is ignorant of that aspect of himself which is passively determined. This extreme of activity is the fault through which he destroys himself. It is not a moral fault – indeed, Sophocles seems to have been particularly careful to make clear that Oedipus is not a bad man - note his considerable public-spiritedness (13) and his care for the city even at his own expense (443). The focus is not on crime and punishment, but rather on a flaw which causes an individual to bring about his own destruction.

The action of the play shows how Oedipus, through his supremely competent activity, brings himself to the most passive state of all, for he does not really make himself passive, but rather reveals himself as having already been the pollution in the city. His action in the play does not create a new situation so much as it merely shows that he is in a situation in which there is nothing to be done, and it is after this revelation that he blinds himself. The man who started from such a commanding height that he addressed the citizens as “children” – tekna, the first word of the play – is in the end reduced to the state of Teiresias, who is led about by a boy.

The final lines of the play drive the message home: an excessive orientation toward activity misses the mark. Pure activity might be a genuine possibility for the gods; it leads to self-destruction in humans. Oedipus, who earlier said “one must rule” (629), now finds himself saying “one must obey” (1516), although his obedience is still forced upon him. As the play comes to an end, the point is made given twice:

Oedipus: I must obey, though it is bitter.

Creon: All things are good, at the proper time.

...

Oedipus: Do not take my children from me.

Creon: Do not seek to be master in everything.

It is difficult to imagine a play more relevant to our own time than Oedipus the King. Its central character functions very well indeed as a representation of the state of affairs to which modern science has delivered humanity. Just as Oedipus had attained a peak of power and success, and thus confidence, as a result of his ability to make things happen using discursive reasoning, so too has our own peculiar form of discursive reasoning, modern science, delivered to us a power far beyond the imaginings of earlier generations.

A bit more than a century ago, it would have been possible to talk about how we had the confidence of Oedipus, but if we can no longer do so, it is because the truth that lurks at the heart of Sophocles’ play has begun to loom on our horizon. Science allows us to control and manipulate nature, but a central image of the play – of Oedipus lacking a proper relationship to his own nature, to his own self as passively determined – points to a reality: nature is not only something beyond us that we control, but is also something within us to which we are subject. The power to undo nature’s arrangements can also be the power to undo ourselves. (As C.S. Lewis put it in The Abolition of Man, “Man’s conquest of Nature turns out, in the moment of its consummation, to be Nature’s conquest of Man” – and might I recommend my post on Lyons and Lewis for the reader who wants to hear more about that book?)

If we were to utterly destroy ourselves in a nuclear catastrophe, or with a virus from an out-of-control lab experiment, or by not-quite-succeeding in engineering our own nature, or by means of some kind of climate disaster – none of that would surprise Sophocles, at least if such situations are considered in their fundamentals. I’m inclined to think it’s about what he would expect, given our current situation.

Even after the great wars of the last century, after the atom bomb and the Holocaust helped shatter the illusion that scientific progress could only be good – even after all this has made itself felt, we nevertheless continue to have the situation to which Mary Harrington called attention at the start, in which the truth that Sophocles would teach us is being ignored. The new trans-humanist path aims precisely to be master in everything. Skin colour? Eye colour? Height? Your genes? If science can’t change all of these for you just yet, the day when it can may not be so far away – and plenty of people are working hard to bring that day nearer. More than that, the notion of choice – that is, of actively determining something for oneself – is now thought by many to be of paramount importance, to the point of perhaps being held sacred in some circles. Perhaps surprisingly, the last century failed to bring us to a standpoint from which the sort of vision presented by Sophocles in Oedipus the King could become widely accepted.

---

This post is a sort of intermission, a break from my proper focus on Plato and Thucydides in relation to our own time, but it is meant to contribute something to that focus. The reader may have noticed above that in setting out two different conceptions of human nature, Mary Harrington pointed implicitly to a history, for the first view of what it is to be human – the imago dei – was an older Christian one, while the other view – “mastering imago dei” – is much newer, something that has arisen as (and because) the older Christian order is collapsing. This implicit history mirrors what we have seen in both Plato and Thucydides: an older order with its own ethical understanding is fading away, while something quite new rises in the resulting void. In the analogous history of ancient Athens, no less than today, the notion of mastery was central to the newer view of things, a standpoint that privileged activity over passivity. Recall as well an observation made by Harrington as she described the new view of what it is to be human: as we upgrade ourselves through technology, nobody conceives of any upper limit or endpoint to this process. That is, there is an infinity at work here, an abandonment or absence of any boundary or limit. All of these ideas – a striving for mastery, radical activity, infinity or the absence of limits – all lie at the heart of the works of Plato and Thucydides that we have been considering, and all come together in a further fundamental matter: tyranny. (The book, pp. 163-165, summarises these themes, but there will be more to say about them in what follows.)

(To give credit where it is due: my reading of Oedipus here is indebted to one of my teachers, Wayne Hankey, a theologian who had also reflected deeply on tragedy. Reading Bernard Knox was also helpful. I would also like to thank Zahira Patel, whose feedback on this piece gave me some much-needed encouragement towards publishing it.)