Of Lyons and of Lewis

How Warnings of a New Evil in the 20th Century Were Anticipated in Antiquity

(This post is part of a series which seeks to relate the Athens of the late 5th-century BC to our own time. If you want an overview of the larger picture, of which this post is a piece, you might want to start with my introductory post.)

Those who do not spend a great deal of time online may have missed a hidden gem of the contemporary internet, the essays of the pseudonymous writer “N.S. Lyons.” The subjects of these essays are wide-ranging, but all are related to the notion of an “Upheaval” which has three main aspects: ideological changes sweeping the West, the rise of China, and a technological revolution consuming the whole world. Lyons is a gifted, and often entertaining, writer, and appears to be particularly well placed to reflect upon these changes, for in addition to the outlook of an educated person, he also shows some familiarity with both the inner workings of the US government and with Chinese affairs. Lyons’ own introduction to his essays can be found here. (Alas, the series is now going to be paused for quite some time, but there’s a good deal to read there in the meantime.)

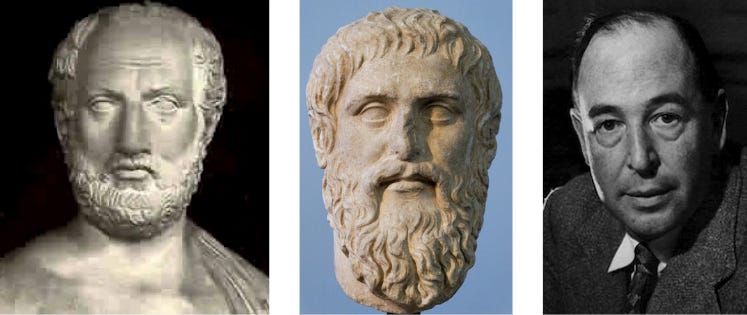

My favourite Lyons essay, “A Prophecy of Evil,” concerns the work of J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. In it, Lyons reviews the work of these two writers of fantasy novels insofar as it brings out a particular form of evil, and suggests that they saw more deeply into the problems of our present situation than celebrated dystopian authors such as Orwell or Huxley. The essay was of particular interest to me because I had seen a good deal of its content before, during my study of Plato and Thucydides. A look at the ground common to these ancient and modern figures should be worthwhile in itself, but it can also serve as an instance of a more general view concerning the value of studying the classics that I once heard from a distinguished classicist and philosopher: in the ancient world one often encounters phenomena that anticipate contemporary realities, but in a simpler form, so that one ends up with a richer understanding of what is peculiar to one’s own time.

In what follows, I will focus on C.S. Lewis as Lyons presents him, primarily in relation to The Abolition of Man, a little book that sets out an important argument directly. Lyons also discusses That Hideous Strength, a novel that treats much of the same material in literary form; I shall touch on it as well. The reason for my focus is that in Abolition, Lewis gives an explicit statement of the logic by which he sees a terrible progress unfolding, and his statement can very nearly be taken as an account of developments we see in Plato and Thucydides. The connection is remarkable because Lewis was concerned with developments he saw (or feared) arising out of twentieth century science. As ‘scientific’ progress proceeds in the twenty-first century, his worries seem all the more prescient, and Plato and Thucydides all the more relevant.

Three themes will give us a view of the similarities between Lewis and the two ancient Athenians. The first is the what Lewis calls “debunking,” a process that finds an ancestor in the theme of custom and nature (nomos and phusis) in Thucydides and in Plato’s Gorgias. The second concerns the result of this ‘debunking:’ in Lyons’ words, “starting from the insistent attempt at pure objectivism we arrive at pure subjectivism.” Specifically, the result is a view of the world focused on individual whim and therefore pleasure, an outcome that we also find in antiquity. A third point of connection comes in the sort of response that Lewis thinks necessary, something that he holds in common with Plato.

(A) Debunking: Custom and Nature

Lyons gives a concise summary of the view with which we will be concerned here: he describes “the belief… that any moral feelings or pangs of conscience are merely subjective experiences and what would today be called ‘social constructs,’ while the real world is purely material, and therefore purely materialistic. To be ‘purely objective’ is therefore, in this view, to focus only on the material, and dismiss the rest as non-existent.” Let us see how this view, or something like it, is brought out in Lewis, in Plato and in Thucydides.

Lewis, in Abolition, notes an enthusiasm among the intellectual class for what he calls ‘debunking,’ that is, for seeing through the pretensions of any judgments of value, whether moral or aesthetic, so as to show that they are mere feelings. His first example comes from a book for schoolchildren. The authors take the case of someone looking at a waterfall and finding it sublime, and declare that this is in fact a mistake: the waterfall is not actually sublime; it is in fact our feelings that we are attempting to describe with this statement, and nothing at all about the world beyond them. This sort of debunking can be applied very widely indeed, to any value judgment including all notions of good and evil, right and wrong. The procedure allows people to believe themselves clever on account of having seen through conceptions of good and evil that ordinary people take to be sound reasons for judgment and action.

However, Lewis is a bit too sweeping when he looks to the past: “until quite modern times,” he tells us, “all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it – believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.” All men? Perhaps not quite all. The practice of “debunking” had a predecessor in antiquity, one that we can see arising in Thucydides’ account of the political life of Athens, and that we also find being put under the microscope by Plato.

The first view we get of this predecessor is in Thucydides, in his record of what is known as the Mytilenian debate. In 428 BC, the city of Mytilene rebelled against Athens, its imperial master. After the revolt had been put down, there was a debate in Athens to decide what punishment should be meted out to the newly reconquered city. At first, the assembly resolved on the murder of all Mytilenian men, and the enslavement of the women and children, but there was soon a second debate in which the Athenians reconsidered this measure. Of the many speeches given in this second debate, Thucydides presents to us his reconstruction of two of them, one from Cleon, the other from Diodotus.

Cleon is an advocate of the original brutal policy. The aspect of his speech that concerns us here has to do with law or custom (i.e., nomos in Greek): he tries to present the original decision as settled law (nomos), and to present those who would change it as excessively clever innovators (“experts” or “elites,” one might say today). Cleon is made to speak as follows: “ordinary men usually manage public affairs better than their more gifted fellows. The latter are always wanting to appear wiser than the laws [nomoi], and to overrule every proposition brought forward, thinking that they cannot show their wit in more important matters, and by such behaviour too often ruin their country; while those who mistrust their own cleverness are content to be less learned than the laws [nomoi], and less able to pick holes in the speech of a good speaker; and being fair judges rather than rival athletes, generally conduct affairs successfully.” (iii.37.3-4)

It is worth drawing attention to the anti-intellectual tone of these remarks, a tone that would be all the more evident if I were to quote the speech at greater length. The suggestion that less intelligent people ought to be the ones who conduct affairs is certainly a remarkable one, perhaps remarkably foolish. In the wider context of Thucydides’ History, however, these remarks take on another aspect, and we can begin to see this if we consider a bit of the opposing speech.

Diodotus confronts an audience that is at once angry at the Mytilenians for their rebellion and also hesitant at the prospect of inflicting too savage a punishment. He wants to move them toward mercy. The tactic he adopts in response to this situation involves a novelty. He paints a picture of human nature according to which all people are moved by natural compulsions such as hope and greed, a picture that reminds us that all people tend to make mistakes, and he claims that laws and customs are insufficient to restrain our natural drives once they get going: states may have set down the death penalty for certain crimes, but who commits a crime in the expectation that he will get caught? Diodotus concludes that “it is impossible to prevent, and only great simplicity can hope to prevent, human nature [phusis] doing what it has once set its mind upon, by force of law [nomoi] or by any deterrent whatsoever” (see iii.45). Here we have the theme of custom and nature (nomos and phusis), and custom is understood to be powerless in the face of nature.

Applied to the matter at hand, Diodotus’ argument is effective, but perhaps too much so. It suggests that trying to make a terrible example of the Mytilenians would be futile, but it also suggests that the Mytilenians themselves are guiltless. After all, they’re only human, and thus subject to the same drives of human nature as anyone else, drives whose consequences are apparently “impossible to prevent.” Athenian anger at the Mytilenians would thus seem to be misguided.

Diodotus carries the day, and the Mytilenians are spared, but the ending of the episode is not such a straightforwardly happy one as it might at first seem. Diodotus has introduced what will turn out to be a double-edged sword: he has used nature to undermine the claims of human custom (or ‘law’). In regard to the immediate case at hand, this is a source of mercy, but within a bit more than a decade, the same line of thought will provide a foundation for an atrocity. (It is also worth noting that Cleon was already playing around with the idea of custom or law, as he tries to pretend that a decision made the day before is somehow settled law that it would be inappropriate to change: the suggestion is that what is happening here is not merely a matter of an innovation of one man, Diodotus, but is the result of a more general destabilisation of norms.)

The problem is that if we make appeals to nature, as Diodotus does, appeals to customs or laws are always going to seem insubstantial by comparison: yes, we may have set up a bunch of rules that describe the world as we might want it to be, but whatever rules we may set up, people will always be driven by their basic impulses – they can’t help it. Such impulses are real and substantial in a way that customs, which are now seen to be mere human inventions, are not. If such considerations seem to absolve the Mytilenians of any ‘guilt’ for rising up against their Athenian overlords, no less can they absolve all people in all circumstances of responsibility (and thus guilt) for anything at all. The whole of normative, ethical life is thus threatened with dissolution. The most famous episode in Thucydides shows us where this can lead.

A bit more than a decade after the Mytilenian affair, the Athenians show up in force at the small and independent island city of Melos, demanding at the point of a sword that the islanders become subject to the Athenian empire. Just as Diodotus did, the Athenians invoke a natural state of affairs to sweep aside all appeals to right and wrong, that is, to sweep away appeals to human customs. Above all, they remind the Melians that “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” No less than the natural drives of Diodotus, this is an appeal to the way things really are, to a natural reality. The Melian response, which is an appeal to custom, seems pathetic by comparison. They protest, for example, that “you should not destroy what is our common protection, namely, the privilege of being allowed in danger to invoke what is fair and right.” The conclusion of the episode drives home just how insubstantial the Melian response is, for they receive precisely the brutal treatment that Cleon had wanted to inflict on the Mytilenians: the Athenians conduct a successful siege of Melos, and “put to death all the grown men whom they took, and sold the women and children for slaves, and subsequently sent out five hundred colonists and settled the place for themselves.”

What is of interest to us in all this is the fact that the Athenians, by means of their appeal to the natural behaviour of “the strong,” are absolved of any guilt or responsibility for what they do, which is just what Diodotus’ appeal to nature did for the Mytilenians. In fact, talk of “guilt” or “innocence” is eliminated altogether by the appeal to nature – just like in the “debunking” that Lewis described. But this liberation from ethical constraint will soon prove to come at a terrible cost for Athens. As the Athenians free their own natural impulses from conventional limits, they begin to act not only brutally, but also foolishly. Soon their greed leads them to launch an ill-considered large-scale attack on Sicily, where one of their commanders betrays his city, leading to the annihilation of the expeditionary force, a result that Thucydides believes played a central role in the eventual fall of Athens. The commander in question, Alcibiades, whom we will consider more closely below, is a sort of paragon of liberation from convention, and his betrayal of his city is just the sort of thing that follows naturally from that liberation. (See also pp. 82-84 in the book.)

Recall at this point the anti-intellectual aspect of Cleon’s words that we saw above. In hindsight, there is reason to look more favourably on his words there than one might have thought from a narrow reading of the Mytilenian debate on its own. The clever arguments of Diodotus, which pit nature against custom, have the potential to wipe away the conventional basis of human life, and thus contain a seed of great evil, an evil that will eventually consume Athens. The “ordinary men” that Cleon favoured could hardly have produced a worse result in the end than their more gifted fellows. (This sort of thing – an apparently straightforward phenomenon that takes on another aspect when considered in a wider context – is altogether typical of Thucydides.)

I want to draw attention to this point that Cleon gets at least partly right, because it aligns with something we see in Lewis: the problem, in his view, is a sort of perversion of human intellect, a cleverness that only really sees superficially, and that thus produces a sort of “progress” that gradually produces serious problems on a deeper level (i.e., the very abolition of normative life that we get from the ‘natural’ arguments of Diodotus and the Athenians at Melos). Lyons notes the appropriateness of a central symbol of That Hideous Strength, a disembodied head from which the technocrats take their orders. For Lewis (who is explicitly following Plato on this point), adequate normative thought cannot be attained with a head alone. Rather, “as the king governs by his executive, so Reason in man must rule the mere appetites by means of the ‘spirited element’. The head rules the belly through the chest – the seat… of emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments.” Perhaps Diodotus’ clever use of nature to overrule custom could be thought analogous to a head without a chest.

Let us turn now to Plato’s Gorgias. The dialogue is based around a development that culminates in the argument with a fellow named Callicles. What Thucydides communicated implicitly, Callicles says right out. He begins by setting out the distinction between custom and nature (nomos and phusis), declaring that these are generally opposed to one another, and continues as follows: “in my view those who lay down the rules [nomoi] are the weak men, the many. And so they lay down the rules [nomoi] and assign their praise and blame with their eye on themselves and their own advantage. They terrorize the stronger men capable of having more; and to prevent these men from having more than themselves they say that taking more is shameful and unjust… But I think nature [phusis] itself shows this, that it is just for the better man to have more than the worse, and the more powerful than the less powerful. Nature shows that this is so in many areas – among other animals, and in whole cities and races of men, that the just stands decided in this way – the superior rules over the weaker and has more. For what sort of justice did Xerxes rely of when he marched against Greece, or his father against the Scythians? … I think these men do these things according to nature – the nature of the just [phusis… tou dikaiou]; yes, by Zeus, by the rule of nature [nomos … tes phuseos], though no doubt not by the rule [nomos] we lay down” (483b-e).

Callicles’ natural justice seems simply to be describing a reality that anyone can observe: the powerful do in fact have more than the less powerful, and as he says, we can see this sort of thing playing out among animals and in human conquerors. By contrast, when we speak of customs or conventions, we are talking about rules that people have agreed upon between themselves, and we are precisely not talking about a reality anyone can observe. Customs are mere human creations, they describe what people might want to be the case rather than what actually is. Accordingly, they are insubstantial in comparison with realities of nature. When Callicles complains of “papers, trickery and spells” (484a), it is precisely this insubstantiality that he’s focused on – and his words parallel the dismissive reference of the Athenians at Melos to “unseen things, prophecy and oracles, and other such things as cause ruin through hope” (v.103.2, my translation). Thus when Callicles speaks of the better person ruling the worse, he echoes the Athenians at Melos, who spoke of the strong ruling the weak, but more than this, he sees the same significance in that distinction as they did: we are dealing with what actually happens in the real world, not with some imaginary desired world.

Clearly, the ‘social constructs’ to which Lyons alluded above line up with the conventions (nomoi) of Callicles, and also with the same word in Thucydides. Of course, having revealed convention (nomos) as something entirely dependent on the whims of humanity, and having attained the objectivity of the perspective of nature (phusis), there is a problem: on what basis might we act at all? Most people act because of their belief in conventions, which tell us which actions are better than others. Once these are gone, what basis is there for living a life, for any action at all? Callicles has an answer to this problem, and it has a deep resemblance to the result that Lewis sees coming about as a result of “debunking.” This brings us to our second theme that connects Lewis with the ancients.

(B) From Objective to Subjective

N.S. Lyons, we recall, described the rather paradoxical result of debunking as follows: “starting from the insistent attempt at pure objectivism we arrive at pure subjectivism.” That is, once we have accepted the view that all value judgments are mere feelings rather than descriptions of some reality of the world – and this applies equally to feelings about beauty, good, evil, right and wrong – we seem to have attained a more accurate and objective view of the world. We have purged it of the confusions brought about by our feelings, and can begin to see things as they really are. But a paradoxical result of this is that when we turn to the question of what might justify or motivate any kind of action, all we have is feelings: “all motives that claim any validity other than that of their felt emotional weight at a given moment have failed... Everything except the sic volo, sic jubeo [thus I will, thus I command] has been explained away. But what never claimed objectivity cannot be destroyed by subjectivism… When all that says ‘it is good’ has been debunked, what says ‘I want’ remains.” (This could actually serve as a largely accurate account of the logic unfolding over the course of Plato’s Gorgias and of the first book of the Republic.)

What is more, those who find themselves in a position of power may at first “look upon themselves as servants and guardians of humanity and conceive that they have a ‘duty’ to do it ‘good’.” But of course there is no ‘duty’ or ‘good’ any more, only feelings. Will the powerful do all they can to support the flourishing of their fellows, or will they torture and exterminate millions, or something else entirely? It is no longer possible to say that any of these paths are better or worse than the others, only that certain individuals might feel something to be better or worse. As this reality gradually makes itself felt, we get to a point at which the powerful “come to be motivated simply by their own pleasure.” (Recall at this point all the talk of gradual change in my first two posts.)

This path, including the move from “the insistent attempt at pure objectivism” to “pure subjectivism,” can be seen in both Plato and Thucydides. When I first began to see it in these ancient texts, it had confused me, because it does not initially seem to make any sense. The objective and the subjective are quite different – perhaps even contradictory – things, are they not? Why was I repeatedly seeing both of them, one after the other, in what otherwise seemed to be a single coherent development? In Thucydides, the point is not initially so easy to see, almost as if the author is trying for the first time to make out an unfamiliar shape. In Plato, it shines forth more clearly, but the point is the same. Reading Lyons’ essay was exciting for me partly because it confirmed these things I thought I was seeing and got me to think them through a bit more thoroughly (see p. 261-262 of the book for my initial reflection on the matter).

We saw above how the Athenians of the Melian Dialogue appeal to the right of the stronger as a fact of the world, using this allegedly realistic focus to brush aside the merely conventional objections of the Melians. Immediately after this ‘objective’ moment – and clearly connected to it (see the book p. 59 for the most direct links) – we see that this same Athens is characterised by a radical focus on the subject as she sets out on the Sicilian expedition. The point here is a large one, and I intend to return to it in a subsequent post, but we see this focus above all in Alcibiades, the man who is represented as decisively moving the Athenians to sail on Sicily, and who then plays a decisive role in that expedition’s catastrophic result.

Alcibiades is characterised by specious rhetoric, that is, by an ability to bring about a conviction within people without regard to the facts of the case in objective world, and he shows himself to be particularly concerned with appearances at the expense of reality. Both of these involve a focus on the human subject rather than on the world as it really is. For example, he boasts of his great expenditure at the Olympics and at home, saying that such displays make Athens look powerful; while recommending the Sicilian expedition, one advantage he sees is that “we will be seen” to sail against Sicily, as if that spectacle would itself constitute a significant result; when discussing the battle of Mantinea, he declares that although the Spartans won the battle, they have not yet regained confidence (an example of empty rhetoric if there ever was one). What all such remarks have in common is the notion that making an impression on people is the crucial thing; whether the impression corresponds to reality is beside the point. Accordingly, we have here a focus on the subject – apparently the precise opposite of the focus on an objective view that characterised the Athenians at Melos.

Nor is this focus on impressions or appearances confined to the words of Alcibiades: Thucydides makes clear that it characterises the situation in Athens as a whole as she sets out for Sicily. There is, for example, the scene in which the Athenians see off their fleet at the Piraeus: when they think of the danger ahead, as their ships depart, they comfort themselves not with deeply considered reflections on the power of their force relative to the enemy it will confront, but instead by focusing on the great sight of the fleet before them, and the splendour of its outfitting (vi.30-31). This focus on appearances constitutes once again a turn towards the subject. (Again, I will return to this point in a future post.) The “objective moment” of the Melian dialogue, then, is immediately followed by the “subjective moment” of the Sicilian debate and the expedition that follows, just what Lyons saw in Lewis.

Plato shows us the same phenomenon, again rather more directly than Thucydides. We saw above how Callicles aimed at an “objective” account of justice, one that was based in nature rather than in mere custom, but as Socrates investigates what is behind all this, he brings out just how far Callicles will take a certain form of individualism, which is explicitly motivated, in the end, by the very same subjective factor that Lewis saw: pleasure. That is, having begun with a claim of pure objectivity, Callicles ends up with a motivation confined entirely to the subject. (Thrasymachus, in the first book of the Republic, follows a similar path and ends up in a similar place, but we will not concern ourselves with him here, on his relation to Callicles, see the book, pp. 248-251.)

In both Plato and Thucydides, then, we begin with a focus on objectivity, and end up with subjective factors. If this presents a rather surprising parallel to the situation described by Lewis, there are also significant differences.

As we saw above, Lewis lays out a process that will unfold naturally as people internalise the view that ordinary human values are susceptible to ‘debunking.’ When people act after this disenchantment, at first the earlier, given norms will influence their behaviour to a considerable degree. As time passes, however, these norms will lose their influence. What is then left to drive action? The will of the individual, and whatever it happens to desire. The overall movement of Thucydides’ history, as well as both Plato’s Gorgias and the first book of the Republic, each show us just such a process unfolding. (I have already written about the place of this process in each of these works, for example in my first post.)

At this point, however, Lewis and Lyons see things in the modern world that are not really found in ancient Athens. Prior to the modern era, the notion that human nature could be changed did not have wide currency. More recently, however, human nature has sometimes seemed quite malleable indeed, and to some it seems that the possibilities here have no limit. Thus it might seem that future generations could be shaped through education (and perhaps, one day, also by chemical manipulation) into something altogether new by those who have grasped the nullity of existing customs and who are also backed by the full power of modern science. Values, of course, will now be understood as natural phenomena, with no basis in anything other than the will of those shaping the future, who Lewis calls “the Conditioners”.

Lewis saw things going further than this, to an attempt to supersede and get rid of natural life. The character Dr. Filostrato, in That Hideous Strength, looks forward to the day when trees can be replaced by artificial aluminum trees, and birds by artificial birds, whose song can be switched on and off at will. In fact, Filostrato dreams of being able to get rid of organic life as such, as people upload consciousness to something non-biological. This, of course, would allow the new ‘humanity’ to be a purely human construction and to conquer death. None of this is dreamed of in Plato or Thucydides – and yet, it does represent an intensification of what we do find in them, above all of the extreme and unbounded activity, essentially connected to tyranny, that forms an essential and inextricable aspect of Callicles, Thrasymachus and Alcibiadean Athens. (On this activity, see the book, pp. 263-265.)

The fact that Lewis sees things going further at this point than his predecessors in antiquity did explains the character of the inhumanity he sees arising. For Plato, people who fully liberate themselves from convention are falling back from humanity into something bestial: Thrasymachus is thrice compared to a wild animal. Lewis, on the other hand, when he looks ahead to men who have fully taken on board the debunking of ordinary values, sees people who are trying to leave behind the world of animals, with the aim of becoming post-organic beings of pure intellect and will. When he says of such people, “they are not men at all,” he has in mind a failing precisely opposite to that seen by Plato: an intellect that has divorced itself from the natural rather than having fallen back into it.

There is a further aspect of Lewis’ vision that departs from what we see in antiquity. Lewis posits a hatred arising out of the void left by the ‘debunking’ of all conventional values – i.e., out of the notion that there is nothing good. “I am inclined to think that the Conditioners will hate the conditioned,” he says, and (as Lyons shows) in That Hideous Strength this tendency finds expression in the character of Dr. Frost. Plato does not seem to have seen anything in his own time that went this far. On the contrary, he seems to see all people as moved by things they believe to be good. It becomes clear that Callicles actually believes things other than just pleasure to be good, while Thrasymachus has his own peculiar conception of the good (to agathon – 343b), in that he is most fundamentally oriented around getting what he takes to be good things. Lewis sees people really stepping into the void in a way that Plato did not. Thus we get the prospect of people acting from a hatred, which arises out of the view that there is nothing good. It is remarkable what a close parallel to this hatred Lyons is able to find in contemporary events, in the figure of Adam Lanza, whose nihilistic philosophy realises some of Lewis’ worst fears. (Lanza is the one who shot 20 children and 6 adults to death, and then himself, in 2012; the reader should turn to Lyons for a look into this episode and its connection to Lewis.) In antiquity, it was Thucydides who provided the parallel in events; we touched on the most famous example above, the case of Melos.

Lewis also sees a tendency toward the deliberate perversion of normal human instincts and reactions, something connected to modern science. The basic idea here is familiar enough: science, as it seeks an objective view of things, requires that we leave behind and even repress our natural and conventional reactions. For example, if someone were to stand in front of a crowd and cut open his stomach and start removing his intestines, there would be automatic expressions of horror and disgust – but biologists or doctors, when trying to understand an animal by dissecting it, or when operating on a patient, are accustomed to do just this sort of thing without any reaction of disgust. A standpoint that seeks purely scientific objectivity thus aims at killing conventional reactions as a matter of principle, at least in certain respects. (For an exposition of how this idea is worked out in That Hideous Strength, I once again direct the reader to Lyons, whose commentary on Mark’s training into a standpoint of “total objectivity” is particularly illuminating - and note how this continues the idea mentioned above, of a view of the world “purged ... of the confusions brought about by our feelings”). I don’t think this sort of thing really has a proper predecessor in antiquity – the worry there is rather that we are going to allow our natural tendencies to run free without being limited by convention, not that we will deliberately and consciously seek to turn away from them.

Once again, it is simply extraordinary how Lyons is able to find examples from contemporary society that line up so closely with Lewis’ concerns from eight decades ago. For example, he points us to Yuval Noah Harari, who has so internalised the new, post-debunking view of the world that he speaks of “useless humans,” and asks, “What do we need humans for? Or at least, what do we need so many humans for? … At present, the best guess we have is keep them happy with drugs and computer games.” He also understands our time as a sort of second industrial revolution, and he notes that the first industrial revolution allowed those countries that underwent it fast enough “to subjugate everybody else.” That is, our new era is understood here in terms of the subjugation of some people by others, an echo of the tyranny mentioned explicitly by Callicles and Thrasymachus; it also constitutes a theme in Thucydides. Harari further tells us that the product of this second industrial revolution will not be machines, but rather humans themselves. This new, post-human ‘humanity,’ which will be a construction of humans, is a step beyond anything imagined in antiquity, but it is just what Lewis foresaw. Indeed, Harari foresees the abolition of man, just as Lewis did: “we are probably one of the last generations of homo sapiens, because in the coming generations, we will learn how to engineer bodies and brains and minds.”

What we have in our own time, then, is a recurrence, but also a deepening, of something that appeared before in ancient Athens, and this happened at a time when Athenian society was undergoing a process of cultural transformation (or collapse) much like our own. The evil that Lyons sees prophesied in Lewis is, in its fundamentals, very much the same as the evil that Plato and Thucydides saw coming to light in their own time. It arises as a result of conventional values coming to seem insubstantial and unreal, and produces a situation in which individual whim, liberated from all constraints, is let loose to do as it wills - a situation in which the strong prey upon the weak, and in which it has become difficult or impossible to explain why they should not. The power given to people by modern science, which vastly outstrips the power of any ancient tyrant, makes the potential for brutality in our own time much worse.

(C) The Response to Debunking

Lewis tells us how cultures and peoples prior to the modern era held “the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is, and the kind of things we are.” He uses the term Tao for this view, using a non-Western term to emphasise its universality. While I’m not inclined to agree with everything Lewis claims for the Tao, what I want to focus on is what I take to be the reasoning by which people, after the appearance of the doctrine of subjective value, should be moved to return to the ‘older’ way of viewing the world, the notion that value judgments describe something about the world, and not just our feelings. The reasoning, as I understand it, is a kind of reductio ad absurdum argument: the result of the doctrine of subjective value is “the destruction of the society which accepts it.” That is to say, it is not the case that Lewis claims that he can demonstrate that when we call a waterfall sublime, we describe something about the world rather than just about our feelings. Rather, we come to know the doctrine of subjective value by its fruits, and reject it as a consequence. This is how we get to the claim that “a dogmatic belief in objective value is necessary to the very idea of a rule which is not tyranny or an obedience which is not slavery.”

This is not an argument with which Plato would disagree. His own doctrine of objective value is put forth in the course of the Republic, and it finds its motivation in the first book of that work, which culminates in the very result – “the destruction of society” – that troubles Lewis. Briefly put, as we progress through the development of the first book of the Republic, we find that the society that could be maintained as a consequence of the doctrine in question at each stage gets ever more fragmented as we proceed. We start with the world of Cephalus, which could produce a polity at peace with itself; when we proceed to the next character, Polemarchus, we find that the doctrine he puts forward would produce multiple camps at war with one another – friends against enemies, factions within a city. The final character, Thrasymachus, contains the move from factions to tyranny, that is, to a society of one person, who aims to dominate and exploit all those around him. A society of Thrasymachans would tend not to be a society at all, but rather a kind of war of all against all (at least until somebody won). So the first book of the Republic traces out the gradual “destruction of society,” as a polity becomes divided and ultimately finds itself broken down to the level of its smallest component part, the individual. Plato’s philosophy is, in part, an attempt to answer this problem: how is it possible to set things up so that society does not tend of its own nature towards its own destruction? His answer is precisely the doctrine of objective value that Lewis talks about, and from the perspective attained by the end of the first book of the Republic, that doctrine can be seen as necessary in the same sense and for the same reasons that Lewis laid out, i.e., the reductio ad absurdum of its opposite. (The rest of the Republic may provide other forms of necessity, but that would be well beyond our current focus.)

Thucydides traces out a disintegration of society that parallels what we see in Plato. Indeed, such a disintegration is a major focus of the work: the Peloponnesian War is not only a story of cities at war with one another, it is also a story of faction, about cities going to war with themselves, and thus ceasing to function as coherent units. The subjective spirit epitomised in, but not confined to, Alcibiades, is the logical endpoint of such a movement, and it coheres in the decisive respects with the tyrant. However, Thucydides only presents a hint of the solution that Plato is aiming at, so I will leave the matter there. (On that solution, see the book, pp. 80-82, on the power of justice, something to which I shall return in a future post.)

The Last Word

The evil observed both in antiquity and in the 20th century is that of a will liberated from all normative limits. It is true that Plato saw some good coming out of all this, and that is something to which I hope to be able to return in a future post. Unfortunately, the good he saw was of an intellectual kind, and would have been little consolation to people living through the times to which he and Thucydides bore witness. Thus a comparison between ancient Athens and C.S. Lewis may help us to understand what is peculiar to our own situation, but it cannot make us optimists.

Finally, there is one further aspect of this connection between Lewis and antiquity that I want to discuss, involving a specific comparison to Plato, and I shall take that up in the next post, on Callicles and Dr. Frost.

(I would like to thank John Leen for his response to this piece, which made me think it might be worth publishing, and also got me to begin publishing this whole series.)