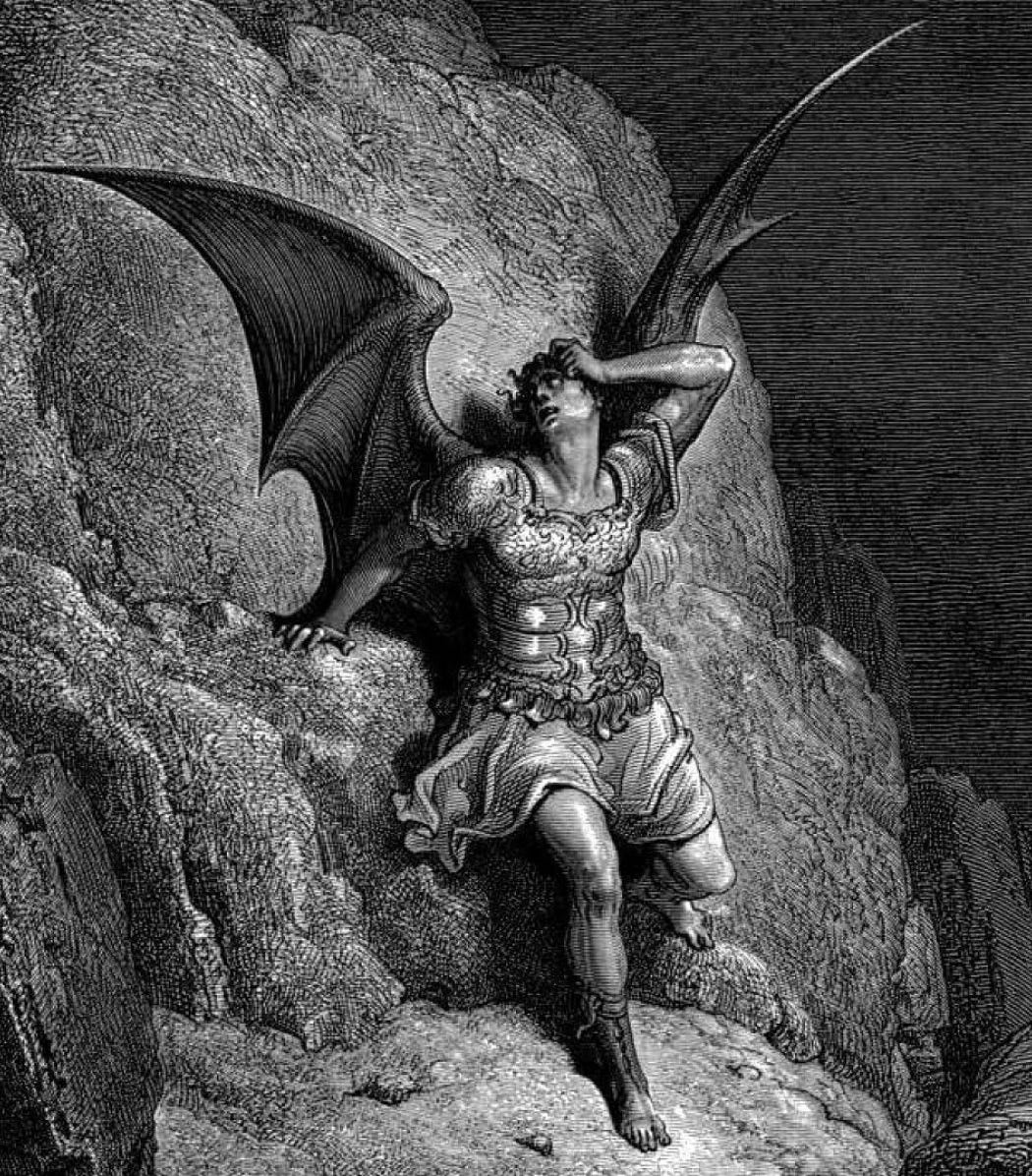

Mary Harrington and Satan

Pre-Christian Reflections on a Modern Predicament

(This post is part of a series which aims to relate the Athens of the late 5th-century BC to our own time. If you want an overview of the larger picture, of which this post is a piece, you might want to start with my introductory post.)

For me, one of the most interesting public intellectuals to appear in recent years has been Mary Harrington. She seems to have made a name for herself primarily on the basis of her peculiar brand of “reactionary feminism,” but she is worth reading more generally for her often profound reflections on the contemporary Zeitgeist. What has made her so interesting to me is the fact that she repeatedly says things that seem to echo aspects of the crisis of ancient Athens, including even the first tentative steps of Plato’s response to that crisis.

(Also, she’s hilarious!)

Here I will focus on one echo of antiquity that we can see coming to light in a piece titled “How Satan Conquered America.” It provides an opportunity to treat several points of connection between antiquity and today. Perhaps more importantly, the connections lie in the third and final stage of the process I see unfolding in the Athens of Plato and Thucydides, and it is this final stage that has unhappily come to seem the most relevant to our own time. This post will be the first of a number that try to open up the third stage in its various aspects.

So what does Harrington mean by her rather provocative title? “At its core,” she tells us, “Satanism is simply the doctrine of untrammelled individualism, shorn of any link to the divine.” Her piece gives a brief history of the development of this doctrine in modern times, beginning with Milton, whose Satan is characterised by a refusal to be ruled. A more recent development of the same idea is found in “the occultist Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), [who] pursued a doctrine of individual will unconstrained by law or stuffy morality.” More specifically, we find in Crowley a pursuit of “the liberation of individual will from taboo, custom, law and even (as practitioners of ceremonial magic hoped) reality itself.” She also discusses “Anton LaVey’s Church of Satan,” which rejected “all collectivist constraints on individual behaviour and emphasise the primacy of individual desire. ‘There is a beast in man,’ he declared, ‘that should be exercised, not exorcised.’”

Harrington shows how these ideas have developed into phenomena that we are accustomed to see around us every day, including even aspects of the modern self-help industry. My own interest in her piece, however, came from another angle. Every detail I have just quoted from Harrington is present at the end of the tale told by Plato and Thucydides about the life of ancient Athens: an unrestrained individualism characterised in part by a refusal to be ruled, the liberation of the individual will from laws and customs (i.e., from nomoi, a word she uses) as well as from any other constraint, and thus an unconscious attempt at liberation from reality itself. Driving all this is the primacy of individual desire. Plato’s Republic also points to cutting of the link to the divine, and to the “beast in man” in the figure of Thrasymachus, who is compared to a wolf, a lion and a “wild beast.” Even the implicit notion of a history, of an idea developing more deeply over the years and culminating in the various elements listed above, provides a link to our two ancient Greeks.

It will, I hope, prove interesting to take a brief look at these points of connection, primarily as they appear in Plato’s Gorgias, which seems to me to provide the most straightforward basis for comparison. I have already provided a window onto the form of individualism we find at the heart of this dialogue, and the equivalent moment in Thucydides, as well as the matter of nomos and phusis (custom and nature), in my piece on Lyons and Lewis, but there is more to say.

---

Consider the figure of Callicles, who stands for the third and final stage in Plato’s Gorgias. By the time the reader of that dialogue has gotten to Callicles, he has already seen Socrates argue against two other characters, and the movement through the three characters has a definite structure, one that brings before us a sort of liberation. First Socrates argues with the elderly Gorgias, and in the course of their discussion, it becomes clear that there exist ethical boundaries the old man will not cross. As Socrates begins to speak with the next character, Polus, it swiftly becomes clear that Polus is willing to push the envelope ethically to a much greater degree than Gorgias, and is willing to express his admiration for the use and abuse of power, even when the talk is of tyrants and the horrific tortures they inflict on others. Callicles, however, is willing to take things further still than Polus. Thus we have a tale of a gradual move beyond the limits of conventional ethical life: Polus will abandon ethical constraints to a greater degree than Gorgias, and Callicles will go farther still. Recall that Harrington wrote of “the liberation of individual will from taboo, custom, law:” it is the same story as we move through the Gorgias, and it culminates in Callicles’ dismissal of such things as taboo, custom or law as “papers, trickery and spells.”

Satan, of course, is known for his refusal to be ruled - “Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven,” Milton has him say. Callicles would agree, but he takes this refusal to be ruled to an extreme that might test even Satan. Consider the following exchange:

Callicles: It is fitting... for the rulers to have more than the ruled.

Socrates: But what about themselves, my friend? Rulers or ruled in what way?

Callicles: What are you talking about?

Socrates: I’m talking about each one of them ruling himself. Or shouldn’t he do this at all, rule himself, but only rule the others?

Callicles: What are you talking about, ‘ruling himself’?

Socrates: Nothing complicated, but just as the many say – temperate, master of himself, ruling the pleasures and appetites within him.

…

Callicles: How could a man become happy who’s enslaved to anything at all?

This is a remarkable thing for Callicles to say, for people who can’t control themselves don’t tend to do terribly well at - well, much of anything. The very idea of self-rule is novel to him. What the exchange shows is just how intent he is on the notion of ‘freedom’ as a liberation from any form of authority. The idea of not being ruled is clearly of crucial importance to Callicles; he wants to adopt the most active standpoint imaginable (an aside: the opposition of active and passive forms a theme that I think important to a number ancient Athenian works, and we shall see in a few weeks that it is not confined to Plato or Thucydides).

This radical focus on not being ruled, in particular in relation to the appetites, points to another aspect of the Harringtonian Satan that we also find in Callicles: “the primacy of individual desire.” On this subject Callicles could hardly be more emphatic: “the man who is to live rightly should let his appetites grow as large as possible and not restrain them, and when these are as large as possible, he must have the power to serve them.” From this, it quickly becomes clear that what Callicles is fundamentally interested in here, the end towards which all else must be directed, is pleasure.

Harrington mentions, in passing, the notion of being liberated from reality itself, and this is something that we also brush up against in Plato. For example, you may have noticed that Callicles’ desire to serve his appetites does not obviously cohere with his desire not to be enslaved to anything at all, and in fact, Callicles’ views are awash in things that do not cohere – recall my post on Callicles and Dr. Frost. In the Republic, as well, liberation from reality comes into view: Socrates has to bring before Thrasymachus the fact that people make mistakes. It is in Thucydides, however, that the idea of liberation from reality itself gets a fuller and more empirical treatment, and I will save that for the next post, which will look into radical subjectivity and its consequences in history.

Finally, there is the matter of how ‘satanic’ individualism is “shorn of any link to the divine.” For this connection to stage three, we must turn to Plato’s Republic, which makes an implicit comment on the relationship of the third stage to the divine (here I repeat a point from my introductory post). The first book of the Republic starts with Cephalus, who has just finished making sacrifices to the gods as the conversation begins, and soon leaves to attend to more sacrifices. The impression is of someone in continual contact with the gods. When the argument moves to Polemarchus, this connection to the divine (and to any other form of tradition) quickly falls away. The third stage, the conversation with Thrasymachus, completes the movement: his only remark touching on divinity comes when he speaks of stealing all things, “sacred and profane.” That is, Thrasymachus is conspicuously impious, especially when taken in the context of the overall development: Plato has been careful to characterise Thrasymachan individualism as quite definitely disconnected from the divine.

---

All this is, I hope, interesting enough, but there is another reason that a comparison of our own time with antiquity is worthwhile, and this concerns a question Harrington raises implicitly: is Satan really bad? “Milton,” she tells us, “saw Satan’s refusal to submit to any law (however ambivalently) as the sin of pride. Now, in our post-Christian world of self-actualisation, pride is no longer a sin. Rather, it’s a vital part of becoming fully yourself.” Because she begins her story with Milton, the two sides are implicitly framed as Christian and anti-Christian. Given that so many today have only ever encountered Christians who have a passive relation to their beliefs, merely going through the motions and responding with a stunned silence to any critical inquiry, Harrington’s framing will, for a great many people, bring with it the implication that one side – the Christian one – hasn’t thought things through, and is based on nothing more than blind faith. The Christian aversion to Satan might thus appear to be little more than an aesthetic preference. If Satan is identified with ‘liberation’ and with an anticipated flourishing, then it’s not hard to see why so many people today might seem inclined towards him.

However, we do not need to appeal to Christianity at all to get an idea of what’s wrong with the ‘satanic’ perspective, for Plato can give us some insight here. Let us return to the Gorgias. Soon after he has established that Callicles is so deeply interested in pleasure, Socrates begins to provide an alternative perspective of his own. He has his own notion of what ‘good’ is, and he bases it on a distinction between doing something at random, and acting while looking to a certain structure or order. I explain his view in my book, p. 157:

The craftsman, we are told, aims to produce in his work some form, setting it in some arrangement, and forcing each part to fit with and be suitable to every other, so as to produce something structured and ordered (503e7-504a2)… Skilled activity does seem to be characterized by the production of order, and this is not only true of human inventions, such as ships or houses, but also of attempts to improve the body, whether through training or medicine. A poorly built house will leak, allow drafts, or collapse; a well-made ship will better survive a storm; a trainer might aim to correct a muscle imbalance. Even the move from order and structure as productive of health and strength (504b-c) is a highly plausible one, and does seem to conform to many facts of life: people who act simply at random, who are utterly unpredictable, seem mad; those who have regulated their passions, and are capable of self-control, can respond reliably to even the most stressful situations. There does seem to be a notion of ‘good’ according to which a great many things – perhaps all – are better off when they attain the order appropriate to their nature; skilled activity aims to produce this.

With this in mind, let us look at Callicles and ‘Satan’ again. They represent the unconstrained will, the primacy of individual desire, and action based on such a principle will not be focused on any structure or order. After all, these would constrain rather than liberate the individual’s will; they would cage the “beast in man.” No, the behaviour of those who seek unbounded subjective freedom will be random rather than ordered, conforming only to the whim of the moment as their desires direct. But when we look to the world, we see that the strongest, the most reliable – in short, the best – things are those that attain their proper order, and this is true regardless of whether we’re talking about ships, houses, bodies – or really anything else. Plato, then, has given us reason to think that the path of ‘Satan’ is the path of weakness and misery, for that is where it must lead, to the extent that we allow it to become the principle governing our lives.

The argument here is simple, but it is far from superficial. It is of central importance to understanding Plato (the Good will be the central concept in the Republic), but I have also found myself returning to it in other contexts. Harrington has recently spoken about the difficulty of getting people today to admit that there is a human nature; Plato’s argument here confronts the more fundamental question of whether we should accept any notion of order, with its inherent limits, at all – but it does seem a necessary first step. The argument here also provides a response to something that came up in my Lyons and Lewis post, namely the ancient Greek problem of nomos and phusis, which seemed to wipe away the normative basis for action (on this, see the book, pp. 156-157). I have also heard Plato’s argument here echoed by priests holding forth on theology. The Christian rejection of Satan begins from reasons such as these, even if it does not end there.

It is not only Plato who sees in ‘Satan,’ as Harrington presents him, a danger to be avoided, and a merely illusory form of freedom. Thucydides treats the same ideas, but he shows how they are effective in history. In particular, he shows how an unbounded subjective freedom found a place in Athens, and how it then produced the total annihilation of the Athenian army at Sicily. I hope that in my next post, I will be able to make all this clear.